The Origins of the Twelve Step Model of Recovery

The Twelve Step model of recovery is understood by many of its adherents to be more than a method for overcoming addiction: it is a spiritual and psychological framework which millions of individuals in recovery have decided to base their lives around. For many of them, this change has led to a marked shift and a noticeable improvement in the quality of their lives. That being said, the origins of this recovery model which has provided much needed relief to so many people around the world are less commonly talked about. The path which the twelve step model followed to get to where it is today is a long one, starting not in a church or hospital, but in a psychiatrist’s office.

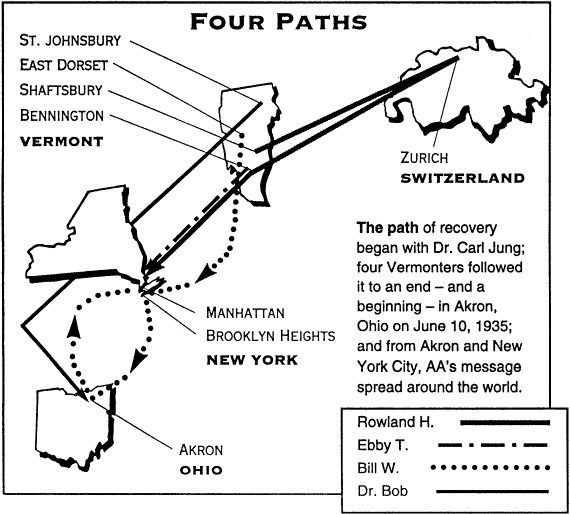

Carl Jung and the Inner Transformation

The roots of the Twelve Steps reach back to the early 1930s, when a man named Rowland Hazard, a wealthy American suffering from an alcohol use disorder, found himself in the office of Carl Jung. Jung pronounced Rowland a “chronic alcoholic” and therefore hopeless and beyond the reach of medicine as it was at the time (a credible opinion, considering Jung's role in the early development of psychoanalysis and then, after he left, of analytical psychology). The only hope Jung said he could offer was for a life-changing "vital spiritual experience"—an experience which Jung regarded as a psychological phenomenon. Jung further advised that Rowland's affiliation with a church did not spell the necessary "vital" experience.

This concept of inner transformation wasn’t new to Jung. He had studied religious experience and myth deeply, believing that true healing often required something akin to a conversion—a deep shift in perception, selfhood, and purpose. For Jung, the unconscious was a spiritual realm as much as a psychological one. Rowland Hazard took this seriously. He sought spiritual rebirth elsewhere, in the Oxford Group

The Oxford Group and the Art of Surrender

The Oxford Group was founded by an American Lutheran Minister, Frank Buchman, in 1921. Buchman believed that fear and selfishness were the root of all problems. He also believed that the solution to living without fear and selfishness was to "surrender one's life over to God's plan". The Oxford Group’s ideas featured surrender to Jesus Christ by sharing with others how lives had been changed in the pursuit of four moral absolutes: honesty, purity, unselfishness, and love (these four absolutes were taken from the Sermon on the Mount). It was in the Oxford Group that Rowland Hazard would find his own personal recovery. The Oxford Group wasn't focused on addiction, but it offered a structured path to spiritual change—one marked by confession, restitution, surrender to God, and the sharing of one's story with others. One of the key tenets of the Oxford Group was that in order to keep one’s conversion, or “spiritual experience” as Jung likely would have referred to it, one had to spread the Oxford Group’s message through means of “personal” evangelism.

This brings us to the next link in the chain, Ebby Thatcher. Hazard was following the Oxford Group’s emphasis on evangelism when he and two other Oxford Group members who knew Thacher heard about him while they were summering in Glastenbury, Vermont, in 1934. Thacher was the son of a prominent New York family who, like many well-to-do Eastern US families of the period, summered in New England, forming lifelong associations and friendships with other "summer people" as well as with permanent residents of the area. Upon learning that Ebby was on the verge of commitment to the Brattleboro Retreat (the former Vermont Asylum for the Insane) on account of his drinking, Hazard and fellow Oxford Group members Shep Cornell and Cebra Graves sought out Ebby and shared with him their Oxford Group recovery experiences. Graves’s father was the family court magistrate in Thacher's case, and the Oxford Groupers were able to arrange for Thacher's release into their care.

While Thacher was put under the care of the Oxford Group, he was for a time put in residence in Sam Shoemaker’s Calvary Rescue Mission, which catered mainly to saving individuals in exactly the sort of predicament he had found himself in. It was Shoemaker who taught his inductees the concept of God being of one’s own understanding. This ultimately led to Ebby Thacher's acceptance of the principles of the Oxford Group and his own sobriety.

Alcoholics Anonymous: A New Expression of an Old Current

Ebby Thacher, in keeping with the Oxford Teachings, needed to keep his own conversion experience real by carrying the Oxford message of salvation to others. Ebby had heard that his old drinking buddy Bill Wilson was again suffering from the same malady which had been haunting him not too long ago. Thacher and Shep Cornell visited Wilson at his home and introduced him to the Oxford Group's religious conversion cure. Wilson, who was then an agnostic, was "aghast" when Thacher told him he had "got religion."

A few days later, in a drunken state, Wilson went to the Calvary Rescue Mission in search of Ebby Thacher. It was there that he attended his first Oxford Group meeting and would later describe the experience: "Penitents started marching forward to the rail. Unaccountably impelled, I started too... Soon, I knelt among the sweating, stinking penitents ... Afterward, Ebby ... told me with relief that I had done all right and had given my life to God." The Call to the Altar did little to curb Wilson's drinking. A couple of days later, he re-admitted himself to Charles B. Towns Hospital. Wilson had been admitted to Towns hospital three times earlier between 1933 and 1934. This would be his fourth and last stay. Thacher visited him there on December 14 and essentially helped Wilson take what would become Steps Three, Four, Five, Six, Seven, and Eight in the Twelve Step Model.

Bill Wilson obtained his "spiritual awakening" going through the steps with Ebby in Towns Hospital where he had his conversion. Wilson claimed to have seen a "white light", and when he told his attending physician, William Silkworth about his experience, he was advised not to discount it. After Wilson left the hospital, he never drank again.

In Akron, Ohio, in 1935, Wilson met Dr. Bob Smith, another alcoholic. Their meeting would become the cornerstone of what would soon be called Alcoholics Anonymous. Drawing from the Oxford Group’s principles but detaching from its explicitly Christian framework (using the principle of “a God of our own understanding,” previously established by Shoemaker), Wilson and Smith began codifying their own approach. The result, published in 1939 as Alcoholics Anonymous, was the Twelve Steps—a synthesis of Jungian psychology, evangelical spirituality, and lived experience.

Where Jung spoke of the necessity of a “spiritual awakening,” the Twelve Steps formalized that journey: admitting powerlessness, making a moral inventory, confessing wrongs, making amends with those you have wronged, seeking conscious contact with a higher power, and carrying the message to those who still suffer.

The Legacy

Today, AA and its many descendants (NA, EDA, SLAA, Al-Anon, and beyond) are often seen as American institutions. Yet their intellectual DNA carries European psychology, evangelical revivalism, and mystical spirituality. From Jung’s couch to the smoky halls of recovery meetings around the world, the Twelve Steps remain what they always were: a map for the kind of psychic change Jung believed was the only cure for a hopeless case.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_W.#

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ebby_Thacher

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oxford_Group

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rowland_Hazard_III